John Brown Massacre Clip Art Man Fight With Swords Clipart

MHQ Dwelling Page

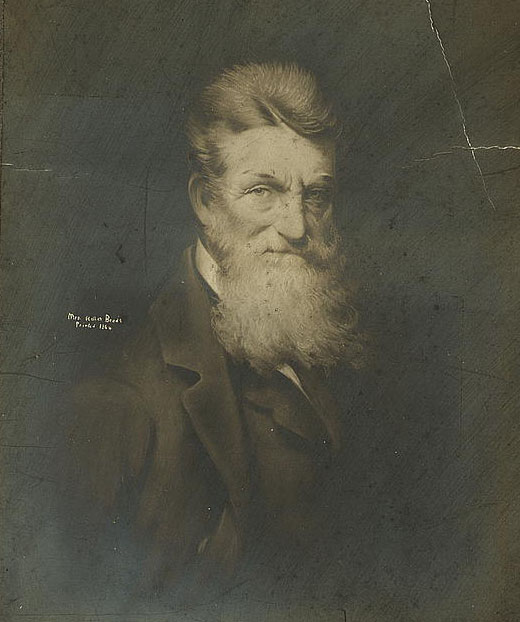

Author Tony Horwitz (Confederates in the Attic) returns to one of his favorite subjects, the Civil State of war, in his forthcoming volume, Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil State of war. Information technology's a history that doubles as a character study of a radical whose human activity of terror carries overtones of 9/xi. "Harpers Ferry seems an al-Qaeda prequel: a long-bearded fundamentalist, consumed by hatred of the U.S. government, launches 19 men in a suicidal strike on a symbol of American power," Horwitz writes. "A shocked nation plunges into state of war."

The excerpt below traces Brown's first campaigns of war and terror, 3 years earlier Harpers Ferry, when he and his family formed a Northern army to fight proslavery forces in Kansas.

* * * *

At about xi o'clock on the brightly moonlit dark of May 24, 1856, James Doyle, his wife, Mahala, and their v children were in bed when they heard a noise in the 1000. Then came a rap at the door of their cabin on Musquito Creek, a tributary of Pottawatomie Creek. A voice outside asked the mode to a neighbour'due south abode. When Doyle opened the door, several men burst in, armed with pistols and big knives. They said they were from the "Northern army" and had come to take Doyle and iii of his sons prisoner.

The Doyles, a poor family from Tennessee, owned no slaves. But since moving to Kansas the preceding fall, James and his two oldest sons had joined a proslavery party and strongly supported the Southern cause. Two of the Doyles had served on the court convened the month earlier at Dutch Henry'due south Crossing on the Pottawatomie to charge the Browns with violating proslavery laws.

Mahala Doyle pleaded tearfully with the intruders to release their youngest captive, her 16-year-old son, John. They let him go and then led the others out of the cabin and into the dark. "My husband and two boys, my sons, did not come back," Mahala after testified. She and John didn't know the identity of the men who came to their door, merely they'd glimpsed their faces in the candlelight. "An sometime man commanded the party," John Doyle testified. "His face up was slim." He added: "These men talked exactly similar Eastern men and Northern men talk."

Before leaving, the strangers asked the Doyles about a neighbour, Allen Wilkinson, who lived nearly half a mile away with his wife, Louisa Jane, and two children. Like Doyle, Wilkinson had come from Tennessee and owned no slaves. Unlike Doyle, Wilkinson could read and write. He was a fellow member of Kansas's proslavery legislature, and his cabin served as the local postal service role.

After midnight, Louisa Jane, who was sick with measles, heard a dog barking and woke her husband. He said it was nothing and went back to slumber. Then the dog began barking furiously and Louisa Jane heard footsteps and a knock. She woke her married man again; he called out, asking who was at that place.

"I desire you to tell me the way to Dutch Henry's," a voice replied. When Wilkinson began to give directions, the human said, "Come out and show us." His married woman wouldn't permit him. The stranger and then asked if Wilkinson was an opponent of the Gratuitous Land crusade. "I am," he said.

"You are our prisoner," came the reply. Iv armed men poured into the cabin, took Wilkinson's gun, and told him to get dressed. Louisa Jane begged the men to let her husband stay: She was sick and helpless, with 2 small children.

"You have neighbors?" asked an older man who appeared to be in command. He wore soiled apparel and a straw chapeau pulled downwards over his narrow face. Louisa Jane told him she had neighbors, but couldn't get for them. "It matters not," he said. Unshod, her husband was led outside. Louisa Jane thought she heard her husband'southward voice a moment subsequently "in complaint," merely then all was yet.

Dutch Henry's Crossing was named for Henry Sherman, a German immigrant who had settled the ford. He traded cattle to westward pioneers and ran a tavern and store that served as a gathering place for proslavery men. He and his brother, William, were feared by Free Country families for their drunkenness and threatening behavior.

On the dark of the Northern army'due south visit to the Pottawatomie, Dutch Henry was out on the prairie looking for stray cattle. Just ane of his employees who lived at the Crossing, James Harris, was comatose with his wife and child when men burst in carrying swords and revolvers. They demanded the give up of Harris and iii other men who were spending the night in his 1-room cabin. Two were travelers who had come up to buy a cow; the third was Dutch Henry's brother, William.

Harris and the 2 travelers were questioned individually outside the cabin, and then returned inside, having been establish innocent of aiding the proslavery cause. Then William Sherman was escorted from the motel. Near xv minutes afterward, Harris heard a pistol shot; the men who had been guarding him left, having taken a horse, a saddle, and weapons. It was now Sunday forenoon, about 2 or 3 a.chiliad. The terrified settlers forth the Pottawatomie waited until dawn to venture exterior. At the Doyles', the first business firm visited in the dark, 16-yr-one-time John found his father, James, and his oldest blood brother, 22-year-quondam William, lying dead in the road virtually 200 yards from their cabin.

Both men had multiple wounds; William'southward head was cut open and his jaw and side slashed. John found his other brother, twenty-twelvemonth-old Drury, lying expressionless nearby.

"His fingers were cut off, and his artillery were cut off," John said in an affirmation. "His head was cut open; there was a hole in his breast." Mahala Doyle, having glanced at the bodies of her husband and older son, could not expect at Drury. "I was so much overcome that I went to the house," she said.

Down the creek, locals who went to the Wilkinsons' cabin to collect their mail establish Louisa Jane Wilkinson in tears. She had heard about the Doyles and could not bring herself to get outside, for fright of what she might find. Neighbors discovered Allen Wilkinson lying dead in castor about 150 yards from the motel, his head and side gashed, his throat cut.

At Dutch Henry's Crossing, James Harris had also gone looking for his overnight guest, William Sherman. He found him lying in the creek.

"Sherman's skull was separate open up in two places and some of his brains was washed out past the h2o," Harris testified. "A large hole was cutting in his breast, and his left hand was cut off except a picayune piece of skin on one side."

News of the murders along the Pottawatomie spread speedily through the district. A day after the killings, John Chocolate-brown was confronted by his son Jason. A gentle man known as the "tenderfoot" of the Brown clan, Jason had stayed behind with his brother John Inferior while the others headed to Dutch Henry's.

"Did you have anything to practice with the killing of those men on the Pottawatomie?" Jason demanded of his male parent.

"I did not do information technology, just I canonical of it," Brown answered.

"I recall it was an uncalled for, wicked human action," Jason said.

"God is my gauge," his male parent replied. "We were justified under the circumstances."

This was about every bit clear a argument as Brown would ever make about what became known every bit the Pottawatomie Massacre. He spoke of it rarely, and then only in vague terms that suggested he was culpable without having personally shed any blood. His family hewed to this line. "Father never had whatsoever thing to do with the killing only he run the whole business," said Salmon, the most talkative of the four sons at the massacre. "The piece of work was so hot, and so absorbing, that I did not at the time know where each actor was, exactly, or exactly what each man was doing."

The Browns and their allies cast the killings equally an act of cocky-defense: a preemptive strike against proslavery zealots who had threatened their Free State neighbors and intended to damage them. The Browns' defenders likewise denied whatsoever intent on their part to mutilate the Kansans. Broadswords had been used to avoid making noise and raising an alarm; the gruesome wounds resulted from the victims' attempts to ward off sword blows.

Simply this version of events didn't accord with bear witness gathered subsequently the killings. Mahala Doyle and James Harris both testified that they heard shots in the night. And "former man Doyle" was found with a bullet hole in his brow, to go with a stab wound to his chest.

The about plausible account of Brownish's deportment came from a family member who wasn't at that place: John Junior. Though initially opposed to his father'southward mission, he later wrote a lengthy defense force of it. Until tardily May 1856, proslavery forces in Kansas had committed about all the violence, killing six Free State men without reprisal. Every bit the Browns and their Free State allies stewed, John Junior said, they realized the enemy needed shock treatment—"death for decease."

But the Pottawatomie attack wasn't only a matter of evening the score in Kansas. Those sentenced to die must exist slain "in such manner equally should exist likely to cause a restraining fear," John Junior wrote. In other words, the killing should so terrorize the proslavery military camp equally to deter future violence.

In this light, the massacre made grisly sense. Like Nat Turner, the nearly haunting figure in Southern imagination, Brown came in the night and, with his Northern army, dragged whites from their beds, hacking open heads and lopping off limbs. The killers wore no masks, obviously stated their allegiance, and left maimed victims lying in the route or creek. Pottawatomie was, in essence, a public execution, and the bulletin information technology sent was chilling.

"I left for fear of my life," Louisa Jane Wilkinson testified in Missouri, where she took refuge later her husband's killing. The Doyles besides fled a day after the slaughter.

So did many of their neighbors. And news that v proslavery men had been, as ane settler said, "taken from their beds and almost litterly heived to peices with broad swords," spread like prairie fire across Kansas. "I never lie down without taking the precaution to fasten my door," a settler from Southward Carolina wrote his sister presently after the killings. "I accept my rifle, revolver, and one-time abode-stocked pistol where I can lay my manus on them in an instant, besides a hatchet & axe. I have this precaution to guard against the midnight attacks of the Abolitionists, who never brand an attack in open daylight."

Pottawatomie had clearly succeeded in sowing terror. Only it failed to produce the "restraining fear" that John Inferior believed to be its intent. Instead of deterring violence, the massacre incited information technology.

Let Slip THE DOGS OF State of war! read the headline in a Missouri border paper, reporting on the deaths. Upwardly to that indicate, the Kansas conflict had generated a great deal of oestrus just relatively lilliputian bloodshed. At present, in a unmarried stroke, Dark-brown had about doubled the body count and whipped upward his already rabid foes, who needed little spur to violence.

Not for the last time, Brown acted as an accelerant, igniting a much broader and bloodier conflict than had flared before. "He wanted to hurry upwards the fight, always," Salmon Dark-brown observed of his father. "We struck but to brainstorm the fight that we saw was being forced upon us."

The number of killings escalated dramatically in the months that followed, earning the territory the nickname "Haemorrhage Kansas." In early June, x days after Pottawatomie, Brown struck again, joining his ring with other Costless Country fighters in a bold dawn attack on a much larger force of proslavery men. This marked the showtime open-field combat in Kansas, and the offset example of organized units of white men fighting over slavery, five years earlier the Civil War. The Battle of Black Jack, equally it became known, was a dislocated half-day clash involving almost a hundred combatants. Information technology ended with the surrender of the proslavery men, who were fooled into believing they were outnumbered. "I went to accept Quondam Brown, and Erstwhile Brownish took me," the proslavery commander afterwards conceded. He surrendered not only his men but also a valuable store of guns, horses, and provisions.

Black Jack also brought greater attention to Brown, who kept the Northern press beside of his campaign, sometimes taking antislavery journalists with him in the field. One of these was William Phillips, a New York Tribune correspondent who rode with Brown afterward the battle. "He is not a man to be trifled with," Phillips wrote, "and there is no i for whom the border ruffians entertain a more than wholesome dread than Captain Brown."

"He is a strange, resolute, repulsive, iron-willed inexorable one-time human being," Phillips added, possessing "a peppery nature and a cold temper, and a absurd caput—a volcano beneath a covering of snowfall."

Brown'south growing renown came at great cost to his family unit. His son-in-police force, Henry Thompson, was shot in the side at Black Jack, and nineteen-yr-sometime Salmon Brown sustained a gunshot to the shoulder soon subsequently the battle. Life on the run, subsisting on gooseberries, bran flour, and creek water flavored with a little molasses and ginger, wore downwards the outlaw band. "We have, like David of old, had our dwelling house with the serpents of the rocks and wild beasts of the wilderness," Brown wrote his wife in June. Three of his sons became so debilitated by illness that in August he escorted them to Nebraska to recover in safety.

By and then, conflict raged across eastern Kansas. Partisans on both sides spent the summertime raiding, robbing, burning, and murdering, while federal troops struggled to incorporate the anarchy. The violence climaxed in belatedly August, when several hundred proslavery fighters, armed with cannons, descended on the Free State settlement at Osawatomie, where Brown's sister and other family members lived. With only 40 men, Brown led a spirited defense of Osawatomie. Though he was ultimately forced to retreat, Chocolate-brown scored another propaganda victory past fearlessly battling a much larger and better-armed foe.

"This has proven most unmistakably that 'Yankees' will fight," John Junior wrote of the reaction to Osawatomie. His father, slightly wounded in the combat, was initially reported dead, a mistake that only enhanced his aura. The boxing besides gave the Captain a new championship. As a noted guerrilla and wanted man, he would adopt a number of aliases over the adjacent three years. Simply the nom de guerre that stuck in public imagination was "Osawatomie Brown," a tribute to his Kansas stand.

The name also evoked his family'south connected sacrifice in the cause of liberty. Early on in the morning earlier the boxing at Osawatomie, proslavery scouts riding into the settlement encountered Frederick Brown on his style to feed horses. Assertive himself on friendly ground, Frederick evidently identified himself to the riders. 1 of them was a proslavery preacher who blamed the Browns for attacks on his property, and he replied by shooting Frederick in the chest. The 25-year-old died in the road.

His father learned of the slaying while rallying his small force to repel Osawatomie'southward invaders. Frederick'southward older brother Jason took part in the battle, and at its end, he stood with his father on the bank of the Osage River, watching fume and flames ascension in the altitude as their foes torched the Gratis State settlement they'd fought and so hard to defend.

"God sees it," Brown told Jason. "I volition die fighting for this cause." He had made similar pledges before. But this time Dark-brown was in tears, and he mentioned a new field of battle to his son.

"I will conduct the war into Africa," he said. This cryptic phrase spoke clearly to Jason, who knew "Africa" was his father's code for the slaveholding South.

Excerpted from Midnight Ascension: John Brownish and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War, by Tony Horwitz. Copyright © 2011 past Tony Horwitz. Reprinted by organisation with Henry Holt and Company, LLC. All rights reserved.

Source: https://www.historynet.com/john-browns-blood-oath/

0 Response to "John Brown Massacre Clip Art Man Fight With Swords Clipart"

Post a Comment